Researchers at Stanford University report they’ve fashioned an innovative sensor made up of chemical gels that communicate with the environment that can reveal the forensic history of water contamination. Specifically, the sensor can record when chemicals appear in water and in what concentration, without electronics, creating a simple and inexpensive sensor to find unknown sources of contaminations in streams.

The team reports the sensor could very much be useful for studying geothermal or petroleum reservoirs deep underground. In these kinds of environments, electronic sensors are typically ruined by the high temperature and pressure.

How the sensor works

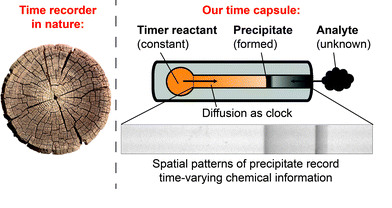

The sensor “time capsule”, as the researchers dubbed it, is made up of a clear plastic casing the size of pinkie where two tiny tubes filled with a carefully chosen gel are placed. The two tubes communicate through a common reservoir , which contains a chemical that diffuses, or moves through the gel, at a predictable rate. This is the timer.

Credit: Stanford

Credit: Stanford

The other end of the tube is open and thus is exposed to the environment, allowing chemicals to seep through the water and diffuse.

The Stanford researchers demonstrated the time capsule by placing it in a solution which began as clear water. Later it was contaminated with lead over time. The lead reacted with the two gel substances inside the capsule, leaving a permanent mark. The researchers liken this to a barcode that can then be scanned.

The scientists envision using this current version of the capsule to locate the unknown source of a chemical contamination in a stream.

In the field, engineers would throw the capsule into the water upstream of the contamination and let it flow downstream. At some point the capsule would interact with the contaminant and leave a time stamp on the capsule.

Based on the flow rate of the stream and the diffusion rate of the timing chemical, engineers would be able to estimate where along the streambed the capsule first encountered the contaminant. That would help them focus the search for the source.

“The capsules would have to be small enough to fit through the cracks in rock layers, and robust enough to survive the heat, pressure and harsh chemical environment below ground,” Sindy K.Y. Tang, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering

The findings appeared in the journal .

Because the time capsule doesn’t contain any mechanical or electrical parts, it’s a lot cheaper than anything on the market right now. Moreover, it’s fit for use in environments where not other sensors are viable. Next, the Stanford team plans to the time capsule technology smaller and experiment with different gel materials to expand the chemicals that can be sampled.

“Although the work is still at an early stage, we showed for the first time that it is possible to use chemical diffusion to record information about the time chemical reactions occurred, without the need for external power,” Tang said.