I was telling you, in a previous article, about forensic entomology – the branch of forensics which deals with the study of insects. The branch is extremely diversified and complicated, especially given the 1.3 million species described so far, which account for about two thirds of all species on the planet (that we know of).

Entomology basics

North America, although ‘poorer’ in species than other continents is still host to 100.000 species of insects, responsible for pollinating flowers, food crops, fruits and vegetables. They are also useful for other reasons, mostly production of honey and wax, silk, shellac, etc. Still, although only 3% of all insect species are considered pests, their impact can be quite significant, and can cause starvation and other major issues.

Entomology, like virtually any branch of zoology, uses a binominal nomenclature system – basically classifying any organism using two words: the genus, and the species. Insects are members of the Arthropoda phyllum, which represent 3 quarters of all living organisms on Earth – so it’s easy to understand why the job of an entomologist is so harsh.

Forensic entomology

Forensic entomology has three branches: medicocriminal entomology, urban entomology, and stored product entomology.

Urban entomology is the study of insects and mites that affect humans living in cities on a regular basis; mostly, this deals with insects and insect related issues concerning legal aspects of man-made structures. Home stored product entomology is typically the study of insects which infest foodstuffs stored in the home – but applied, of course, in a forensic environment, mostly focused on insect damage to stored commodities. Mediocriminal entomology is used to study violent crimes.

Of course, the most ‘advertised’ and known branch is mediocriminal entomology; you’ve probably seen Gil Grissom, the main character of CSI Miami. The thing is, most of what he does is true, though greatly stretched. A forensic entomologist deals with the pathological examination of human (and animal) remains, and can determine the time of death, post-mortem interval (PMI). He can also provide a limited, preliminary understanding of the cause of death, and can determine if the body has been moved. Insects can also be used in toxic studies (entomotoxicology). For example, in the analysis of maggots, empty puparids or larval skin cast, a forensic entomologist studies the bioacumulation of toxins – but this is only a qualitative and not a quantitative measurement.

There is an evergrowing demand for mediocriminal entomologists, though not of a great magnitude, but in order to qualify for this position, individuals must have serious knowledge from a myriad of fields, including biology, chemistry, toxicology, and of course, forensic expertise.

A day in the life of a forensic entomologist

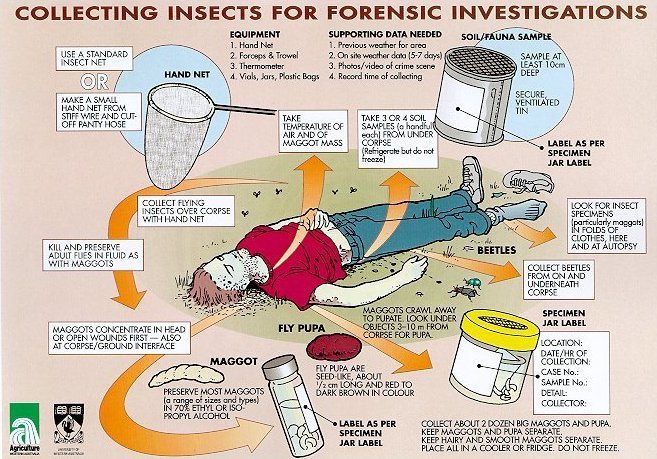

Forensic entomologists take copious amounts of data from the crime scene; they put a whole lot of time and energy into the process – and they have to be extra careful, because of course, everything they collect has to be able to stand in court, and they work with some of the most frail pieces of evidence. First of all they have to take note of the climate and environment in which they work, an imperative in order to estimate what insects could be involved in the process – different conditions have a different impact on the insects and their life cycles.

Then, they have to make many observations on the crime scene itself, typically total maggot mass, maggot development, placement of the maggot mass on the body, temperatures, and stage of decay; they have to do all this while following the chain of evidence and avoiding any sort of contamination.

Typically, a forensic entomologist has to follow certain rules. First of all, he has to take close-up photos of insects, mite bites and the stage of decomposition. They have to take pictures without the flash, which often makes them ‘flash-out’, and add a scale to the pics. Then, they have to collect insects – at least a spoon of them, from at least three different areas. Then the insects have to be killed (sadly) with hot water, then stored in ethanol, and placed in a refrigerator. He often uses nets, sticky jars, and all sorts of chemicals used in the process.